top of page

Search

The Challenges of Researching Native Tales

Traditional Native lands of the Northeast, including the Wabanaki Confederacy. Wabanaki likely comes from the Passamaquoddy word...

Ben Hellman

Oct 9, 2021

Teaching Gluskabe: Wrestling with American Values

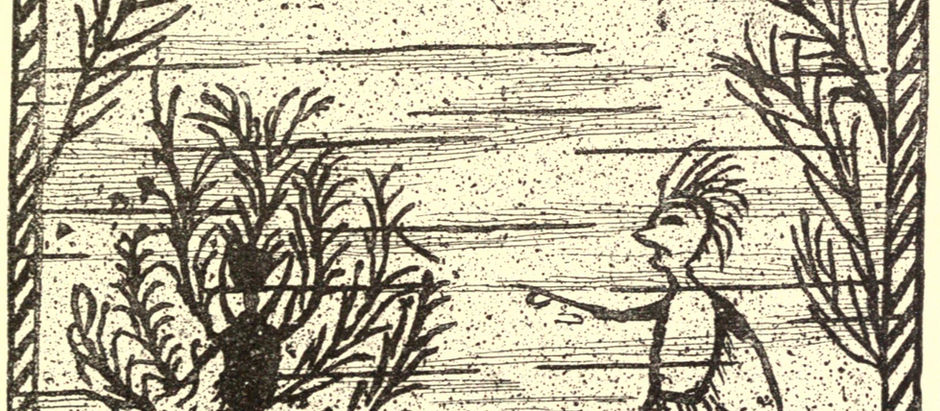

Gluskabe turning man into a cedar tree. Scraping on birchbark by Tomah Joseph 1884. (Image from Wikipedia). I never read a piece of...

Ben Hellman

Sep 19, 2021

Timely Lessons from the Land of the Coming of the Light

Just before dawn, Rockport, Maine August 26 (photo by author). The Native tribes of New England formed the Wabanaki Confederacy....

Ben Hellman

Sep 6, 2021

PRACTICAL MYTHOLOGY

Benjamin Hellman's Blog

bottom of page