- Ben Hellman

- Jun 28, 2021

Updated: Jul 1, 2021

The author contemplating another round of phantasmagorical excess at the House on the Rock, Spring Green, Wisconsin. Photo by Rachel Hellman.

It is no wonder that Neil Gaiman, in search of the ultimate incarnation of phantasmagorical American kitsch, landed on Wisconsin’s House on the Rock. I haven’t seen everything our great and varied country has to offer, but it is hard to imagine anything being more of what the House on the Rock is. If the dark carnival from Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes was permanently frozen in place and had grown a bit musty from lack of housekeeping, it might be this mildly disorienting, excessive attraction.

I just revisited the house a bit more than two decades after my first experience and this time lived somewhat vicariously through my wife’s first-time responses, the element of surprise being somewhat a part of the experience. The surprise is simply that anyone would build what the eccentric collector Alex Jordan and the successive owners of the site have wrought. And though I knew what was coming—it had been seared in my mind for twenty-three years—it is impossible to say I was not freshly taken aback or would not again be taken aback if I made the pilgrimage to the house again two decades hence.

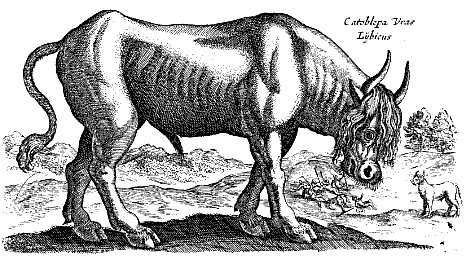

It would be reductive to call the House on the Rock a museum (and perhaps an insult to both the house and actual museums), but it is certainly a theatrical cabinet of curiosities. It is hard to imagine that the Louvre houses a more extensive display of legendary and mythological creatures, but also that the Louvre staff would not spot and remove the fantastically garish creatures if one managed to sneak a few in there. The angels at the Louvre are not department store mannequins fitted with wooden wings and evening gowns from the 1970s; the grotesque chimeras are not lacquered carousel animals, however fantastical. If there is a female nude fitted with a unicorn head in any world class museum anywhere, please send me the details in a private message!

Crown of the Doll Carousel

When at the House on the Rock, one quickly learns that ours is not to reason why. Photo by Rachel Hellman.

Yet the house is not simply a strange collection of strange objects (though it is certainly that). For instance, the collection of (likely faux) scrimshaw tusks and horns, or (again, likely faux) historical firearms is not notable for any particular object, but rather that they are too numerous to fix on one in particular. With the historic firearms, for instance, one finds oneself walking down a corridor of seemingly ancient guns in cases placed end to end in rows starting at the floor and surpassing one’s height. It is as if the objects were a patterned wallpaper made three dimensional. Authenticity isn’t really the point, though everything that is meant to be real looks reasonably real to the layman. Not many of the objects are labeled anyway. Here multiplicity and particularity take on a spectacle of their own.

An Overwhelming Menagerie

The visitor can be disoriented and even overwhelmed by certain spaces in the House on the Rock. Photo by Rachel Hellman.

What the house does for large-scale legendary spectacle is probably also not to be outdone. Photographs do not really capture the scale of what is billed as the largest indoor carousel in the world, nor the sea battle between the giant squid and the whale, which one ascends a three story ramp around to appreciate the finer points. The very top was roped off, barring the view inside the whale’s mouth, but I recall a dinghy inside with an adult-sized bewhiskered mannequin dressed in a yellow fisherman’s rain hat and slicker. The carousel is populated only with exotic and fantastical beasts: mermaids pulling a carriage, a bare chested female zebra centaur and a myriad of other man-horses dressed as soldiers from various times and places, giant cats and dragons and elephants and unicorn sea horses. The point is that I knew this was coming, but beholding it again, in person, the scale of the thing, bedecked in red chandeliers racing by and seemingly several stories high, made me dizzy.

Gaiman's American Gods

The carousel becomes a portal to another dimension in the television adaptation of American Gods.

Author Neil Gaiman, who made much of the house in his novel American Gods, said in an interview that he came across it in 1992, five years before I did, and did not know what to make of it: “but I loved it.” He said he was determined to write a book and put the house in it. The conceit of the novel is that gods come into being when humans worship them, and when the world flocked to the North American continent, they brought versions of their gods with them that took on a distinctly American hue. In the old world, when people came across places that felt particularly powerful or magical, they would choose those places to worship. In these places shrines and temples and churches and cathedrals were built. But in America, instead of shrines, people built roadside attractions and the House on the Rock is one of the most powerful places in the country. Gaiman’s gods and human protagonist meet at the house and interact with several exhibits that are still there today and they end up at the great carousel, which transports them to another realm. I suspect that certain people who have been fans of Gaiman’s novel are discovering as they read this that the House on the Rock is a real place.

My First Trip to Wisconsin

The author with castmate Emily Abraham in American Family Theater’s Robin Hood, 1997.

I first encountered the house right out of college while working in a touring musical theater production of Robin Hood. My small company had made a circuit from New Jersey, down the coast to Louisiana, into Texas and then north to Wisconsin, stopping in little towns at small and large venues across the American south and Midwest. Sometimes we played in restored (or moldering) vintage vaudeville era theaters whose verve the house seems to recreate. The billboard-sized vintage posters of magic acts of yore in the house’s strange little food court likely played in some of the same theaters (assuming the advertisements weren’t created whole-cloth for the house). The attraction seemed made for me at that particular point in my life, perfect for this group of young men and women who probably hadn’t seen too much of the world at that time. We made a meagre living dressed up in costumes, trucking a bunch of flat boards painted to look like an English forest. We loaded the faux forest into the theater, entertained the children, flopped in what seemed like the same cheap, but clean hotel room and then started the next long van ride to the next city. The house seemed at the time a great life event, a story I must recall the details of to share with friends at home. This was 1997 and I’d left my disposable cardboard camera in the van. If the house had a website at the time, too many images would have overburdened the computing power of modern technology. But you must understand: it didn’t feel like I’d only experienced a roadside attraction. It felt like I was the last witness to the burning of the Hindenburg and bore the awesome responsibility of telling the tale.

Twenty-four years later, and I’ve seen the actual Sherwood Forest and been to the Louvre, and seen many of the actual wonders of the world and yet, I still appreciated the house, even if I smelled the mold and saw the cobwebs the staff had allowed to accumulate, noticed the occasional broken fretwork of the (probably faux) wooden Japanese window screens. This time I encountered the house during a reunion of teachers who had all once won places in a Chaucer seminar in London. The day before revisiting the house I’d sat in an orderly Frank Lloyd Wright house, tasted champagne and partaken of a charcuterie board. In returning these many years later, I discovered I did a good job recalling those details that seemed so vital so many years ago, even if the whole delightful scene was a bit tawdrier than I might have recognized that long ago.

Heritage of the Sea Room

The author and his wife, Rachel, at the bottom and top of the epic battle between the whale and the giant squid. Photos by Rachel Hellman.

Instead of having to wait to share the experience, this time I had the perfect travel companion. Watching my wife’s jaw drop and yet retain its grin, hearing her repeated gasps and ejaculations of “Holy bananas!” told me that the house was still doing the job it was meant to do. Seeing the groups of twenty- and thirty-somethings doing much the same showed me that it wasn’t just us. Others seemed also to share our eventual fatigue, which I can only describe as the weariness one feels midway through a trip to Ikea, where even though one speeds up their pace to break free, there always seems to be another area to get through. We found a young man curled into a ball on a shag-carpet covered bench, likely only thinking he was pretending, as he muttered “It just doesn’t end…” as we entered the sixth or seventh period-themed room dedicated to mechanical instruments self-playing an orchestral suite (this one the Blue Danube) at the drop of a twenty-five cent token in the slot. Every one of these rooms is an overwhelming rococo grotesquerie producing a sensory overload and they just keep coming. Give me a good carnival calliope and I feel satisfied. Give me twenty and make each an immersive experience and my head starts to spin.

A Cacophony of Sound and Detail

A music box room performing music from the Nutcracker Suite. Photo by Rachel Hellman.

And, love it or hate it, all of this seems to be the point. Three hours later with sore feet and wondering whether I would ever want to return (I would, given a new person to watch experience it for the first time) we stumbled to our car, happy to be in the sunlight, happy to walk across something as mundane as a parking lot (even with the colossal vases covered in dragon sculptures that look vaguely as if designed by children). The House on the Rock is probably not for everyone, but for those of us looking for one of the more unusual escapes to a realm of the fantastic, it does transport.