To Catch a Catoblepas by the Tail

- Ben Hellman

- Apr 11, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 19, 2021

Detail of Sludge, the Catoblepas, a wall-mounted sculpture by author, paper mache and mixed media, inspired by an illustration by David A. “DAT” Trampier in the D&D Monster Manual, 1978.

When I was a child there was a dog on my street named Sultan. It was a big, loud German Shepherd; very territorial and on a short chain in the yard at the end of my street. The kids on the street said he used to have a brother named Satan and I was too little to know what Sultan meant, so it might as well have meant the devil. Sultan’s bark penetrated my little body, even from the sidewalk across the street. No one ever walked on the sidewalk in front of his yard. Even if you weren’t afraid of him, his bark would hurt your ears.

And yet I stood and made faces and danced and managed to get Sultan crazy more than once. I never threw anything at him. I could never have gotten close enough. One day Sultan got loose and chased me under the porch of our house. It had slats on the sides and you really weren’t supposed to be able to get under there, but we cut one slat with a saw to make a secret fort. It was dank and full of spiders so this might have been the one time it was useful. I hid under the porch and Sultan paced around, ready to kill me. When he wandered far enough away, I made a break for the stockade gate to my backyard. Sultan got to me before I reached the gate, but he only nipped my little boy's leg.

This is the context in which I first read about the dreaded Catoblepas. I had played Dungeons & Dragons with my friends across the street as early as I can remember. I could have been seven or eight. The Monster Manual was the most thorough encyclopedia of anything I would have read at the time, a most valued guide of creatures from myth and legend. And amongst its much loved pages was artist David A. “DAT” Trampier’s Catoblepas. Trampier’s grumpy, rumpled creature looked like the offspring of a warthog and a brontosaurus. It had the look of having had a few too many rough nights drinking. If a Catoblepas lived on my street, or in the swamp behind my elementary school, it probably would have killed me.

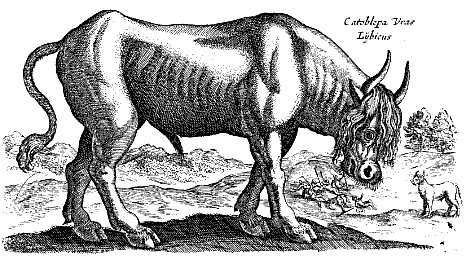

The Catoblepas, by David A. “DAT” Trampier, from a celebration of his art from Heavy Metal’s “The D&D Monster Manual Art of Dave “DAT” Trampier”. Trampier’s story is a poignant one. His art is iconic and recognizable to players of a certain vintage, but despite his success in his 20s, he left behind illustrating and disappeared from public life. After being discovered in a college newspaper story he refused offers to return to the industry until he was diagnosed with cancer. He died in 2014.

The strange nature of Catoblepas was that its gaze could kill you, but its name came from the Greek verb meaning “to look downward,” Romanized from Κατωβλεψ, because its neck was thought to be too weak to hold up its head. So it was very unlikely to look up at you. And therein, I believe, was its charm to me. I had seen Ray Harryhousen’s Clash of the Titans and would not have dared to seek out Medusa. She was fast and wily and very scary (in addition to turning one to stone.) But Trampier’s Catoblepas was a sluggish looking creature and I would have tried to sneak up behind it and whack it with a stick. Which is why it would have probably killed me.

Images of the Catoblepas From Natural Histories

Images of the Catoblepas from historical natural history texts, (left) Der Naturen Bloeme manuscript, 1350, from the National Library of the Netherlands; and (right) by Jan Jonston, from Historia Naturalis de Quadrupedibus, 1614, Amsterdam.

The strange Catoblepas has a strange history. It was not dreamt up for Dungeons & Dragons, or told of in Greek or Roman myths, but was written of quite seriously by Roman naturalist, Pliny the Elder, in the first century of the common era in a serious text, Naturalis Historia (Natural History), a ten volume text that would become the model for encyclopedias. It told of everything that needed to be known about the natural world including animals, but also botany, astronomy and mathematics, and many other topics. Pliny wrote that the Catoblepas was to be found in Ethiopia near the head of the Nile. Pliny’s Catoblepas seems to have been picked up as a verified creature by future natural historians, who added to it a dangerous fiery or poisonous breath. The creature is depicted by some artists as a sort of wildebeest, which may have been its model. Leonardo da Vinci, in the 15th century, gives an account of the creature that is similar to the rest: “It is not a very large animal, is sluggish in all its parts, and its head is so large that it carries it with difficulty, in such wise that it always droops towards the ground; otherwise it would be a great pest to man, for any one on whom it fixes its eyes dies immediately.” In the 19th century, the creature reared its head (or tried to) in the novel The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Gustave Flaubert wrote that its neck was as “long and loose as an emptied intestine.” In the 20th century, Jorge Luis Borges, that lover of things whose veracity may be questioned, included the Catoblepas in his wonderful The Book of Imaginary Beings (which I have also found entirely in a free pdf online).

The Catoblepas Sculpture Project

Various steps towards having a hangable piece of art. For more images, check out the Catoblepas page of this site. (Photos by the author and the author's wife.)

When I met my wife-to-be, we discovered that we both owned jackalopes, small faux-taxidermized rabbits with horns. If that isn't a sign of finding one's soulmate, I really don't know what is. Given that she was a fan of Portland, Maine's International Cryptozoology Museum and I had already had several small art pieces depicting things like the Yeti and a giant squid attacking a ship, we decided to create a cryptid wall. Rachel recently described our décor style as “A Night at the Museum”; we have a suit of armor, tapestry prints, several globes and a collection of fantastic maps of this world and a few fictitious ones. So we weren't far off from having a set of faux-taxidermized fantasy creature wall-mounted heads before we bought our home.

My art projects generally begin when I want something that does not already exist or if it does exists, I can't afford to buy it. To my knowledge, there are no other wall-mounted sculptures of a Catoblepas, but there are some wonderful artists to be found selling fantasy sculpture on Etsy and their own sites and when we started decorating our house, I quickly bought some beautiful pieces that were within my price range and then ran out of options. My Catoblepas project was inspired by the extraordinary art of Dan “the monster-man” Reeder of Gourmet Paper Mache. Reeder’s web tutorials and his Paper Mache Dragons led me step by step through sculpting a head with cloth and paper mache. Of course, Reeder does dragons, and I had already bought a dragon head for my wall. I looked through my trusty Monster Manual for inspiration and found Trampier’s Catoblepas.

Reeder’s resources came close to solving all of my problems, but my Catoblepas needed a long sloping neck and somewhere in my process I thought the creature’s tusks should be made of a polymer clay that ended up being quite a bit heavier than I expected. I did not expect a paper or cloth mache shell to hold it up as far away from the wall as I wanted it so I needed to engineer something that I thought would hold it and yet allow me to bend it to the shape I wanted. This and my worrying about the paint stretched my process out a bit longer than a year, but I finally finished and got it hung!

I named him Sludge because the black and dark blue swirls of his paint looked oil-like to me and because the Catoblepas has come to represent the wastelands, to be a symbol of life contaminated by pestilence. And he looked like a Sludge. He took his place with several other creatures in my barn. Sometimes people suggest that the trophy-like heads lead to the logical conclusion that I hunted these creatures and killed them, but I don’t think of it that way. I am not a hunter and would not kill real animals to mount on my walls. I don’t think of Sludge or the others as dead either. I like to imagine them having conversations when we are out of the house. I also like to think of them as protectors. And because Sludge hangs opposite my front door, I like to think that if anyone comes in who shouldn’t, the intruder will have to roll against death ray or I will find the corpse when I get home.

Comments